[Extra Credit] Classification and Privacy

Hugh Gusterson’s talk on “Secrecy and It’s Discontents” was both informative and thought provoking. Along with laying out the secret goings-on behind the scenes in post war and contemporary American government, he gave a few ideas on how to address and correct the means in which classification and declassification is handled. Gusterson gave three laws of secrecy dynamics, a term which he had coined, to describe the way classification and declassification works.

His first law is that one will classify to avoid embarrassment. The ‘one’ in this statement may refer to some top secret government agency, but I feel that it could also apply to the everyday person. We may choose to post or not post something based on how we feel it would add to our online presence and presentation of ourselves. We may untag ourselves from an unflattering photo or even ask the poster to remove it entirely. This type of discretion is not just something that big governments with big secrets do to keep their public image intact; we do the same. I think one of the feelings that people experience when they find out their data is being tracks is fear of what that data might say about them. They might worry that it would show some embarrassing fact about them or something that they did not want to release in the first place. They worry about who else can see this data. Our reading “Why Counting Your Steps Could Make You Happier” even states that “simply making [our data] available made [the research participants] want to look at it…”

Gusterson’s second law of secrecy dynamics is that one must (should) play it safe. In the context of Gusterson’s research, “play it safe” applied to the decision of whether or not something should be classified. I feel that in the context of everyday life, “play it safe” can be applied to how much data we allow other to track. The basics of computer literacy include knowing what is and is not a scam website for a phishing email. Knowing when to give out your data (in exchange for a youtube video or facebook app), and when not to give out your data (credit card scams, keystroke trackers) can greatly be improved by ‘playing it safe’.

Finally, his calls the third law of secrecy dynamics the “Information Connectivity Creep.” This theory behind this is that all data is connected, so even when one piece of classified, it may touch, overlap, or connect to another piece which is not. Likewise, something that is not classified may be connected to, or partially overlapped by, something that is. So do we need to classify the entire chain of data? Is it sufficient to classify only a single link? During our class on predictive analytics, we walked about how even a few pieces of information could eventually lead us to a specific person, whether the information was website history, spending habits, or daily commute. This data, while seemingly useless on it’s own, is connected to other more personal data. Even if we choose strict privacy settings on different social media sites, we leave a trail of data everywhere we go, leading anyone directly to us. In our reading, How to Detect Communities using Social Network Analysis, we saw just how easy it was for companies, researchers, or even ordinary people to find someone based on their connections and connected data.

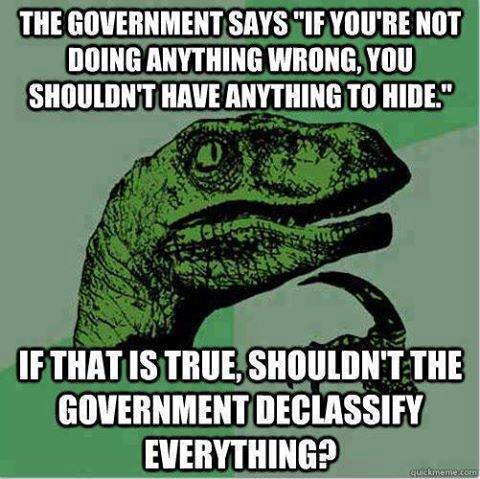

One of the solutions that Gusterson brought up during his talk was the enforcement of a “Classification Budget.” While this was an off-handed comment, said with a bit of a laugh, it struck me as an interesting idea. Gusterson even mentioned how the cost to classify a document was around $200, while the cost to declassify a document is only $1. In class we always tended to bring up the idea of a set time limit on collected data, something that Viktor Mayer Schönberger had brought up himself in his book on big data. Perhaps instead of having a monetary cost on classified documents and data, it would be better to have a time limit on how long it could be kept from the public eye before eventually getting declassified and released. Gusterson mentions that this sort of limit might force the ones doing the classifying to really take into considerations their priorities on what they should and should not keep from the public. In the same way, I think putting some sort of time limit on how long consumer data is kept from the public would force data trackers, and consumers, to rethink how they view their privacy and the commodification and utility of data.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post